ABOUT 關於

For new Chinese-language speakers seeking native materials to engage with, the volume of media available can make it difficult to find works that suit their interests and taste.

This is exacerbated by the fact that original works that grapple with their creators' environment often fall foul of censors, or are deterred from being created in the first place.

The effort to engage is worthwhile. There are a wealth of contemporary artists and thinkers who convey deep human and social insights with dignity, humour, and compassion.

In the case of those whose form of self-expression is hazardous, their willingness to continue regardless makes their voices especially deserving of an audience.

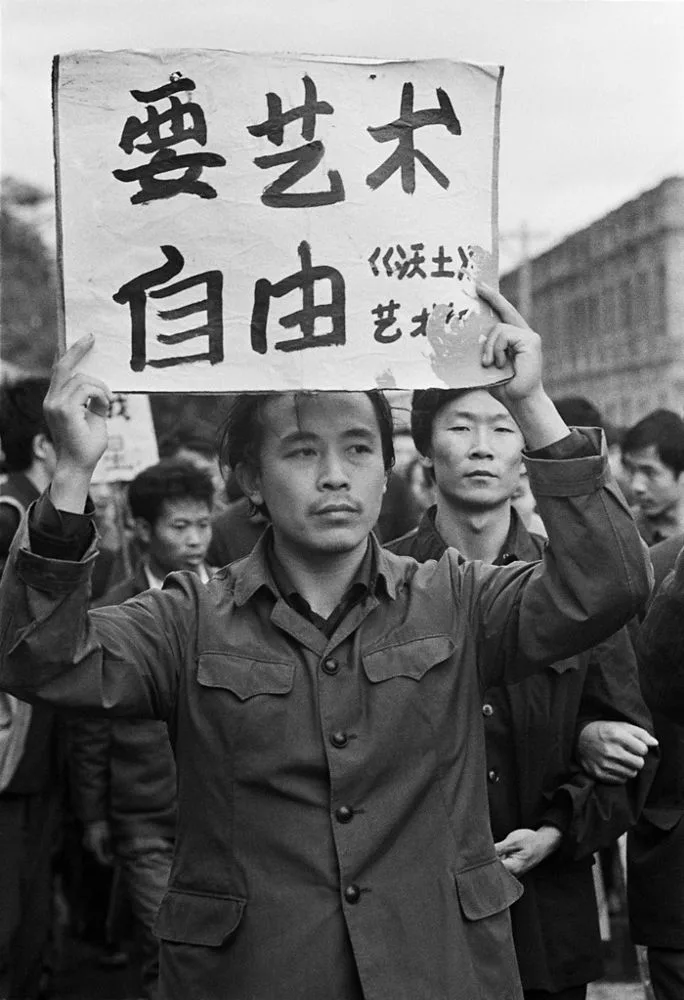

Wang Keping demands freedom for art 《王克平遊行要藝術自由》, 1979,

On the Name 誰爲玄奘

This site is named in homage to Xuanzang 玄 奘 (602 - 664), a Buddhist monk, scholar, and translator during the late Sui and early Tang dynasties, and major contributor to the development of Buddhism in East Asia.

Dissatisfied with the fragmented translations of scripture available to him, Xuanzang defied a ban on foreign travel to visit India, so he could access the original texts.

He returned to the Tang capital Chang'an 長 安 (now Xi'an 西 安) 17 years later with hundreds of texts, and founded an institute to translate them.

His account of his travels, Great Tang Records on the Western Regions 《大唐西域記》 is comparable to Herodotus' Histories in its documentation of the people and cultures he encountered and heard tales of.

Nine centuries after Xuanzang's death, his life inspired Wu Chengen's 吳承恩 classic Ming dynasty novel Journey to the West 《西游記》.

Xuanzang returned from India 《王克平遊行要藝術自由》, High Tang, Dunhuang mural, Cave 103 盛唐敦煌103窟

In the present geopolitical climate, culture is overlooked in the dehumanising process of conflating states' actions with their citizens' attitudes.

Media focus is often limited to politics (understandably) or vulgar incidents (regrettably), and few contemporary Chinese-language voices find an overseas audience through translation.

Among the small but growing number of foreign Mandarin speakers - let alone the other dialects or languages of Chinese - engagement with native cultural output seems rarer still, perhaps due to intimidation by the perceived difficulty of the language, or perhaps to unfamiliarity and lack of exposure.

The ambition of these pages is far humbler than Xuanzang's achievements, but I hope the content shared here will be useful to others in their effort to encounter a diverse range of voices in their own words.